Portraiture Now: Feature Photography

National Portrait Gallery

Eighth and F Streets

11:30 am-7 pm

The current exhibition of contemporary photography at the Portrait Gallery, Portraiture Now: Feature Photography, is a deep and diverse cross-section of possibilities that exist in contemporary photography. The six photographers featured in the exhibit, Katy Grannan, Jocelyn Lee, Ryan McGinley, Steve Pyke, Martin Schoeller, and Alec Soth, all have very different styles and foci in their work, effectively conveying the variety that can be found in photography today. All of the artists publish their work in magazines ranging from Vice, GQ to the New York Times Magazine. Their images help to convey to the public issues ranging from the awkward feelings of inclusion and disassociation at a rock concert to juveniles in adult prisons. In some of the works, the portraits serve as a catalyst to expression of deep ideas that extend far beyond the person depicted, while other portraits delve deep into the psyche of the individual sitter.

Jeff Stackhouse, New York Times Magazine, 9/10/2000, Katy Grannan, Chromogenic print, Collection of the Artist, courtesy of greenberg Van Doren Gallery, New York City; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Salon 94, New york City; Copyright Katy Grannan

Katy Grannan made several early series for which she would advertise in local newspapers for subjects. She would slowly develop a relationship with each sitter and gain his or her trust. The subjects then chose their own poses and locations for the shoot, revealing the individuals’ ideas about themselves and conveying a duality of vulnerability and confidence. Because of Grannan’s sensitivity to the subject, the New York Times Magazine hired her to take portraits for moving editorials. One such piece is Grannan’s portrait of Jeff Stackhouse for the New York Times, which is overwhelmingly apprehensive and poignant. Stackhouse is a fifteen-year-old boy incarcerated in an adult prison. In the photograph, he slouches in an XL striped uniform that looks more like pajamas than prison garb on the acne prone, baby faced young man. The smattering of bright colors and the interesting lines lead the viewer through the composition, finally settling on the boy’s intense sad eyes.

Untitled (girl laying in grass), Jocelyn Lee, Chromogenic print, 2002, Collection of the artists; copyright Jocelyn Lee

Jocelyn Lee is interested in “states of transition, our desire for connection, and the search for personal identity.” Her portraits are intensely personal, awkward and voyeuristic. Lee attempts to uncover vulnerability in her sitters. This type of exposure of a person is in direct contrast to what is generally encouraged by contemporary society, breaking taboos, and the resulting portraits are uncomfortable to look at. Two examples placed side by side at the Portrait Gallery are, “Untitled (Girl Laying in Grass)” and “Untitled (Girl with Dead Birds at Night).” “Girl Laying in Grass” is a pretty young girl lying in a nondescript, cropped field, staring with dead eyes at a large brown moth on resting her hand. Similarly, the untitled “Girl with Dead Birds at Night” is lying in a cropped field, but she stares directly at the viewer with glazed eyes while her hands tightly clutch two dead crows. Both young women are pretty and captivating, totally oblivious to the viewer, and passively absorbed in their own thoughts.

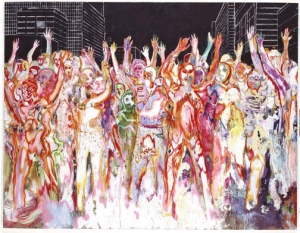

Untitled (Morrissey 20), Ryan McGinley, Chromogenic print, 2006, Collection of Arlene and George Hartman; copyright Ryan McGinley

Anyone who has been to a great rock concert can appreciate the feelings that are related in Ryan McGinley’s photographs. The series at the Portrait Gallery are grainy, strangely colored photographs of audience members at a Steven Patrick Morrissey concert. The pixilation of the pictures seems to pulsate with vibrations from the music, and the, often, unnatural colors convey the estrangement and the high that is unavoidable when speakers and fans are screaming powerful lyrics. In a slightly atypical and subtle photograph, the dark, severely pixilated “Untitled (Morrissey 28),” the subject is almost lost in the near completely black background but saved from obscurity by the slight pinks in her barely visible skin, revealing an obviously beautiful but haunting young woman. This glimpse at the girl threatens to pass and fade away in the transience of the moment and the music.

Sir Ian Mckellen, The New Yorker, 6/1/2007, Steve Pyke, Gelatin silver print, 2007, Collection of the artist, courtesy of Flowers Gallery, New York City; copyright Steve Pyke

Steve Pyke’s close-up, black and white photographs draw on the rich history of photographers. Pyke has photographed some of the world’s greatest thinkers and philosophers both on his own and for the New Yorker, where he is a staff photographer. Pyke’s portrait of the great Shakespearean actor, Sir Ian McKellen (a.k.a. Magneto in the X-men moview) features the actor dressed as King Lear, a part that McKellen coveted for his entire acting career. Representing actors in character is a long-standing tradition—in Edo period Japan prints of favorite actors in character were as popular to collect as prints of favorite Geishas. However, successfully representing the character being acted as well as the personality of the actor is a difficult balance that Pyke seems to have mastered. Pike’s photograph of McKellen shows tenderness, experience and throbbing pain, each of which surfaces in the actor’s face and becomes part of the character he represents.

Cindy Sherman, The New Yorker, 5/15/2000, Martin Schoeller, Digital C-Print, 2000, Collection of the artist, coutesy of Hasted Hunt, New York City, copyright Martin Schoeller

Although Martin Schoeller’s portraits are also close-up images, they have a very different aesthetic than Pyke’s. Schoeller’ portraits are color, deadpan and extreme close-ups. Schoeller is German, and like most contemporary German photographers, he has been influenced by the seriate photographs of Berd and Hilla Becher. Like the Bechers, Schoeller treats all his subjects with the same deadpan aesthetic drawing attention to the repetitive similarities, while scrutinizing the differences in his subjects. Included in the Portraiture Now exhibit are portraits of Barack Obama, John McCain, Angelina Jolie and the elusive, finally unmasked, Cindy Sherman, all through the same honest, impassive lens.

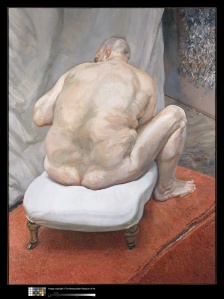

Florence, Paris, France, Fashion Magazine, 2007, Alec Soth, Pigmented ink print, Collection of the artist, courtesy of Gagosian Gallery, New York

Alec Soth has explored many different portraiture projects, but the Portrait Gallery chose to highlight Soth’s portraits of women and his struggle with the inevitable sexual, romantic and voyeuristic qualities that an image of a woman poses when it is a man who takes the image. For example, “Florence,” a Parisian model, is naked in her bed, face devoid of make-up, hair tousled and frail shoulders slouched, her blankets covering her lower body but exposing her small pert breasts. It is a very sexual picture, taken as a ‘before’ for Fashion Magazine; the ‘after’ picture of Florence in the same spot, made up and dressed, is not featured in the exhibit.

These six photographers are covering very different ideas in their work and the Portrait Gallery recognizes that fact by displaying each photographer’s works in separate rooms. However, it is important that the Portrait Gallery brought these photographs together under the roof of one exhibit, because these are the images that are being widely disseminated in magazines to a popular audience who may not think of them in an art context, but an informational one. Understanding the subjectivity and goals of the photographs in popular media is important because photography has a point a view and even if it goes unnoticed consciously, subconsciously a digestion of the meanings behind the image will be absorbed.

-Ophra Paul

Portraiture Now: Feature Photography in on view at the National Portrait Gallery until Sept. 27, 2009.