Paint Made Flesh

The Phillips Collection

1600 21st Street, NW

Tue- Sat 10am-4pm (Thur 8:30pm) Sundays 11am-6pm

The body has traditionally been used as a symbol in painting, often representing spirituality, idealized beauty and power. Paint Made Flesh, an exhibit put together by the Frist Collection, which is resting at the Phillips Collection in DC for the summer, highlights a different side of humanity, the dark conflicted and anxiety plagued side. The show is comprised of works by a multitude of artists who painted between the 1950s and the present day. The show is divided by themes, time periods and locations, making it difficult to decide where Modern ends and Contemporary begins.

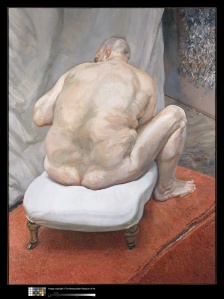

Lucian Freud, Naked Man, Back View, 1991–92, Oil on canvas, 72 1/4 x 54 1/8 in. (183.5 x 137.5 cm). Courtesy of the Metropolitain Museum of Art, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993 (1993.71).

Although the two Lucian Freud’s date from 1988-89 and 1991-92, they are still very relevant and noteworthy. Freud painted from life over long periods of time and favored friends over professional models; he wanted to portray people as they are, not as they are posed to be. Hailing from the Tate Modern, Standing by the Rags is a magnificent portrait of painter Sophie de Stempel, who worked with Freud for eight years and modeled for him frequently. She is half lying, her body resting on a giant pile of Freud’s painting rags and half standing, her feet planted solidly on the hardwood floor. The perspective leans upwards and only a glimpse of a wall helps to anchor the space. De Stempel’s head rests on her right arm, which is arced over a bulge in the pile, cradled as if there were another person lying with her. Her gesture and facial expression seem to exude a comfort and trust that only close friends can have, but she does not have complete confidence in the stability of Freud’s rags and keeps her feet firmly on the ground. The second Freud painting depicts the controversial performing artist Leigh Bowery. Bowery’s back is turned and a curtain blocks the view into the studio, revealing only the distant wall that Freud used as a palette—these compositional choices speak of a more guarded relationship.

Susan Rothenberg, Crying, 2003, Oil on canvas. 58 1/2 x 63 1/2 in / 148.6. Courtesy of Waddington Galleries. x 161.3 cm

Susan Rothenberg and Tony Bevan paint expressively and reduce narratives to articulate deep, focused feelings of stress and tension. Rothenberg’s “Crying,” an entirely red and white painting—her most frequent colors, because of their fleshy human qualities—depicts a head and neck covered by four hands that seemed to have wiped any recognizable features off the face. The face, hands and arms are red and disembodied, and they emerge from the upper left through a white background that has been layered over red. The work captures the haze and wearing nature of depression. Bevan also uses red and white but in a more restrained aesthetic. The red lines that scar and illustrate “Head” seem to be abstract and cluttered up close, but from far away describe strained, stretched, balloon-like face from a skewed upwards perspective. The face seems to float away, falling apart and coming back together on upon each viewing expressing the struggle to maintain clarity in this complicated world.

Jenny Saville, Hyphen, 1999, Oil on canvas. Private Collection, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery. © Jenny Saville

John Currin, The Hobo, 1999, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego.

Jenny Saville and John Currin are both technically accomplished painters who deal with female beauty from totally different perspectives. Saville moved around a lot as a child, always having to adjust to a new location and new people. She sees herself as an outsider and is attracted to unconventional body types. Her studies with a plastic surgeon led to a discovery of the ‘object-ness’ of flesh, and its ability to be sculpted and manipulated, strangely similar to paint. She confronts and embraces her anxieties about being different with monumental paintings, often self-portraits, which have been built up with large areas of paint layered with a roller. “Hyphen” is a double portrait of the artist and her sister, who is resting her head on Saville’s shoulder. Saville’s eyes seem to dare anyone to judge her, effectively guarding herself and her sister—who stares hesitantly but hopefully into the distance—from the harsh world. By contrast, John Currin embraces the long history of objectifying the female figure in his satirical, campy and playfully hedonistic paintings. He celebrates the ridiculousness of the obsession with a perfect female form in “Nude with Raised Arms,” daring his audience to try look away and to decide whether this smooth creamy young body emerging from a milky blackness is Venus, pornography or both. Even more bluntly camp, “The Hobo” makes fun of the way that everyone, even destitute, downtrodden people, are inexplicably beautiful on bad television. Currin does not accept any guilt for his pleasures but instead dutifully recognizes and embraces the beauty and depravity that seem inexorably intertwined in his view of the world.

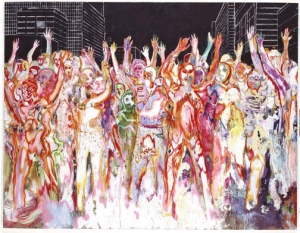

Daniel Richter, Duisen, 2004, Oil on canvas, Image Size: 106 1/4 x 137 3/4 inches. Courtesy of David Zwiner Gallery.

German painter, Daniel Richter is concerned with music, current events, and graffiti culture. The craze that overtakes people when they take drugs and infrared pictures inform Richter’s style and present the point of view of “the paranoid westerner,”* a group which he confrontationally and bravely confesses to be a part of. Richter turns current tragic and violent news events into ambiguous paintings that could be read as celebrations. Using neon energetic colors, he layers the complications of living comfortably as part of first world culture while being surrounded by economic, environmental and military problems, both domestic and foreign. “Duisen” is a painting of a crowd of people with upraised arms, who are melting in violent Technicolor in a black cityscape background. They look as if they could be part of a rave at a concert or victims of some as yet unknown bio-weapon. Duisen is a made-up word that is play between the German words that mean millions and south. Richter is referencing the influx of immigrants to Germany from southern countries, bringing with them political, social and economic upheaval.

Paint Made Flesh includes superlative examples by artists Alice Neel, Francis Bacon, Julian Schnabel, Richard Diebekorn and De Kooning and many others that have come from first-rate museums around the world. The Frist has brought together a phenomenal group of paintings but do not expect to find bucolic and carefree works. This is a challenging exhibit that brings together many different stressful concepts and events. If you leave feeling stressed and overwhelmed than the show did exactly what it intended to do.

-Ophra Paul

Paint Made Flesh is on view at the Phillips Collection until September 1st.

*Schatz, Matthias. “Paranoid Westerner” Daniel Richter Paints Crowds, Harlequins, Terror.” Bloomberg.com (July)

**Although I currently work at The Phillips Collection as a Museum Assistant I was not involved with the planning or implementation of Paint Made Flesh. I am not a Phillips Collection spokesperson; I take personal responsibility for this article.