Artomatic

55 M Street, S.E.

Sun, Wed, Thu 12– 10pm, Fri and Sat 12– 1am

Artomatic, a non-profit, month-long art festival, is celebrating its tenth year filling unused Washington, DC office space with art. This year at 55 M Street, Artomatic has filled eight floors of office space with work by over 1000 visual artists. There is no jury or curator for Artomatic, and anyone can register. This means there are a lot of artists exhibiting in Artomatic whose goals are not to create contemporary fine art, and many who would like to meet that definition, but fall short. In this plethora of art, there are some jewels that should not be overlooked.

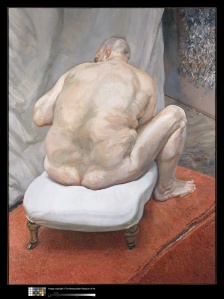

Jamie Wimberly, “Turn Off The Lights At The Tate,” Mixed Media, 2008. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Jamie Wimberly’s “Box Icon Series” consists of small personal altars made of cabinets, wood boxes and deep-set frames that contain objects of contemporary adulation. Often the boxes include votive candles and visual and verbal puns. These altars satirize the things society worships, in particular the female nude, which is one of the most popular subjects at Artomatic. Wimberly’s current project, “Provocations,” which he is showcasing at Artomatic, addresses the excesses and influences of the contemporary art market. One of these “Provocations” contains a votive candle, parted white curtains, a nude female and a dollar bill and is titled, “Gagosian.” This piece shares its name with the notable, Larry Gagosian and his superstar gallery who have had tremendous influence over the art world and what becomes contemporary art. Another work titled “Turn Off the Lights at the Tate” features votive candles, a metal plate that says ‘TATE,’ delicate white partitioned curtains, light switches on a background of deep red wax flowers, and a female nude thinking the word ‘off’ while her arms are braced over her face. The woman seems to be begging for some privacy from the thousands who walk through The Tate Modern every day, scrutinizing the female nudes that have literally become objects forever. The irony is that in creating this satire, Wimberly has once again objectified the female nude.

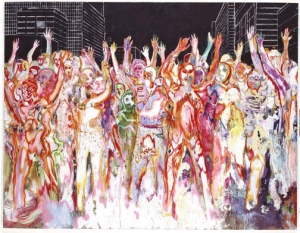

Ben Tolman, The Theatre, 80 x 64 in., ink on board, 2007-2008, Photo courtesy of the artist.

For Artomatic, Ben Tolman printed a reproduction of his work, “The Theater,” an 80 x 62 inch piece that looks like a modernized version of Hieronymus Bosch’s “Earthly Delights,” one of Tolman’s favorite paintings. Tolman’s ink drawings are very intricate, and he only completes about three per year—“The Theater” took nine months to complete. Whenever Tolman begins a new project he starts with a rough idea in mind and does a light sketch in ink of the complete composition. After completing the sketch, he concentrates on individual areas allowing the arrangement and focus to mature organically as he moves throughout the image. The resulting works capture the viewer, refusing release until the entire picture has been taken in. In a large drawing like “The Theater,” this can take some time, so Tolman provided chairs in front of his booth at Artomatic. Also featured at Tolman’s space at Artomatic is a print of a drawing that Tolman completed with artist Lars Peterson as part of the Antipodes project. Antipodes is a collaborative that Tolman started between artists around the world. The collaborative creates large-scale drawings through the mail, each artist adding to the drawing and then sending it to the next artist. A portrait by Tolman will be featured at The National Portrait Gallery as part of their Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition.

Michelle Herman, Applied Research & Technology (installation view, 2008), video and science equipment, 2008. Photo coutesy of the artist.

The collection of science equipment on floor two of Artomatic is the work of Michelle Herman. Her 16mm films are derived from Herman’s study of “Decalcomania,” a painting technique that involves pressing two surfaces together with pigment between them and then pulling them apart, leaving fractal, textured patterns behind. Herman’s videos show the way the ink spreads and moves in water, never repeating the same pattern. The video is displayed on a piece of equipment that looks like it belongs in a science lab, and the video itself looks more like an organism growing and changing than ink blots. Herman is very interested in the way certain bacteria take on the look of ‘decalcomania.’ Herman’s videos are her way of visualizing the controlled chance that exists in nature, in art and life in general. Herman also invites the visitor to participate in her ‘experiments’ by looking through a microscope, which is attached to a live feed camera that displays the unsuspecting visitor’s eye on a screen on the table.

Elizabeth Crisman, Untitled 4, silver gelatin print, 2008. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Elizabeth Crisman restructures elements of the human body and creates new large-scale compositions. By stitching together parts of the male and female body that she photographed, she addresses the psychological, as well as physical effects of the recent trend to transform the body though various medical procedures. In another series Crisman scans or photographs x-ray transparencies, rearranges them onto photosensitive paper and exposes the arrangement as a photogram. Interestingly, the sources for her compositions are completely anonymous, as the transparencies were purchased on eBay.

Tim Tate, I See Myself in a Hollywood Movie, Mixed media, 2008. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Encased in glass like tiny specimens, Tim Tate’s “Video Reliquaries” are deeply enchanting. Each round bubble of glass encloses a tiny video screen and is topped with a small glass sculpture. The smallness of the screen demands an intimate distance from the work, forcing a feeling of deep voyeurism that is most unnerving, particularly in Tate’s “I See Myself in a Hollywood Movie,” a closed circuit video that captures the viewer on the screen. The sculpture topping the piece is an old movie projector. Down beside “I See Myself in a Hollywood Movie,” is a red button that when pressed repeats Gloria Swanson’s famous line in the movie “Sunset Boulevard”—in a gruff voice so soft you have to lean in close to hear—”I’m big… it’s the movies that got small.” This work brings home the absurdity of the reality TV, fame obsessed culture we live in. Tate allows every visitor to be a star (if only on the small-screen), a desire that most participants in Artomatic seem to crave desperately.

J.T. Kirkland, Untitled, Construction-grade plywood, 96" x 144" x 1/2," 2009. Photo courtesy of the artist.

There are very few artists who believe that less is more; even in this bare-bones economy, most contemporary artists (and definitely Artomatic artists) seem to have a Rococo ornamental sensibility. J.T. Kirkland’s installation at Artomatic offers an elegant critique on this subject. Kirkland did not add anything to the plywood wall of his Artomatic space. Instead, he drilled shallow holes in the board, using smaller bits toward the center, focusing attention on the surface itself as opposed to anything adorning it. Kirkland’s work is also a component of a collaborative project at Artomatic called “Space Between.” The project features three artists with similar aesthetic sensibilities who are inspired by each other’s work. The project is still in its initial stages, but it will be interesting to follow as it develops.

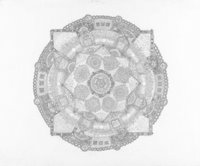

Corwin Levi, Mandala, pencil on paper, 30x22, 2002. Photo courtesy of artist.

Corwin Levi’s drawings provide an intimate look into the workings of his mind. The drawings are astonishingly intricate and take a long time complete. Levi may start out with a few particular ideas but continues to express new thoughts and experiences that accumulate throughout his process. According to the artist, “each piece is both a video and a frame.” They express the time period up till and throughout the completion of the work while at the same time remaining frozen artifacts. The intricate patterns provide a steady composition, but at a closer look, the elements within the patterns contain irregularity and diversity. The components of each drawing must be viewed individually in order to fully appreciate their detail, and stepping back to take in the whole means the losing those details. This can be likened to an attempt to understand a person; it is impossible to understand the whole without losing the intricate details that compose the individual.

Eric Celarier, Untitled, mixed media. Photo courtesy of Katie Bechtold.

Eric Celarier sews small computer parts and circuit boards together to create intricate quilts. His overall design gives the illusion of an aerial perspective of a highly organized and structured city; however, the details of his stitching provide evidence of a human presence in the quilt. By sewing the metal parts on the fabric, Celarier renders the quilt useless in the functional sense, but calls attention to his choice of often disposed and overlooked material.

Alexandra Zealand, Flock, Grapefruit pith, string and wood. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Alexandra Zealand, a sculptor, collects discarded materials including coffee filters, matchsticks, and most recently grapefruit pith. With these materials she explores the human desire to prolong time until death. In her installation at Artomatic, Zealand hung small pieces of dried pith to form a cloudlike sculpture. The delicate structure sways with the slightest movement, and the individual pieces are especially engaging because of their texture and their range in color.

Since there is no curator or jury at Artomatic, there is a lot of kitsch and decorative art. This is not a bad thing, but it is unfortunate that Artomatic is not also thought of as an incubator and a stage for emerging fine artists. In looking at art in this space, it becomes necessary to imagine what an individual piece of art would look like in a gallery or museum in order to contextualize it and decide if it would belong. This tool could also be used the other way around when visiting galleries; imagining a particular work in a space like Artomatic can help diffuse the aura of the gallery and make an accurate decision about the aesthetic merits of the piece.

–Ophra Paul and Alison Reilly

Artomatic will be on view at 55 M St. until July 5th.